Wings of Resolve: The Air Force Journey of WMU Aviation Bronco Tracy Smiedendorf

During a 27-year career in the Air Force, Tracy Smiedendorf logged more than his share of vivid memories.

How about these for the now-retired 1983 alumnus of the Western Michigan University College of Aviation with a degree in what was then known as flight technology:

On "9-11" he was in the Pentagon when the hijacked airliner slammed into the building about 400 yards from his office.

His team of trouble-shooting technicians identified the fuel-contamination "gremlin" that had grounded a fighter squadron of the Honduran Air Force and got the F-5s back into the skies.

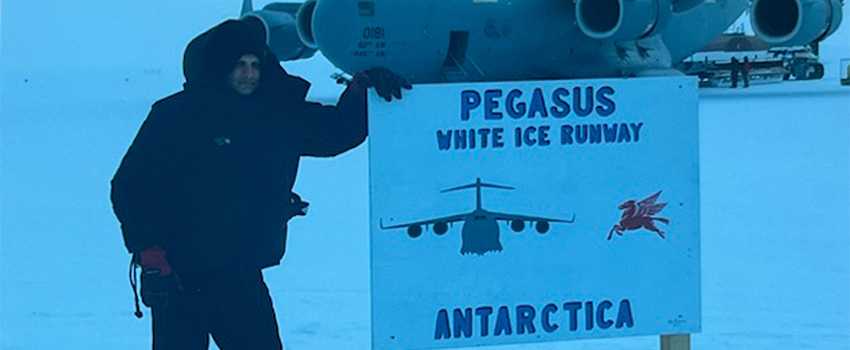

"Summers" (November through February) assigned to McMurdo Station in Antarctica for Operation Deep Freeze when fully-ladened C-17s would land on the ice with supplies to keep a National Science Foundation project running at top speed.

In all, from 1985 to 2012, Smiedendorf wore his Air Force uniform at 13 bases, including other overseas deployments to Japan, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar. More often than not, he was in command of supervising thousands of maintenance technicians working on the inspection, servicing, repair and overhaul of every form of aircraft in the Air Force's arsenal.

And, like Clint Eastwood's "Gunny Highway" character in the film "Heartbreak Ridge," he often learned that "the book" didn't cover all the scenarios and he had to "improvise" -- like during Operation Desert Shield with the "on-the-fly" development of a parking plan for 25 wide-body aircraft on a ramp designed for only five.

Along the way, in his book of career highlights, Smiedendorf was also involved in the genesis and birth of the AC-130J gunship, taking it from the drawing board through modifications, from the inaugural flight to its first missions. He also served a stint as the military assistant to the Secretary of the Air Force, James Roche, duties that saw him write speeches and conduct research for the civilian leader.

Not bad for a fellow raised in the Southwest Michigan community of Niles located due north of South Bend, Ind. The 1979 graduate of Niles High School says he first sampled his future career when "my dad took me to an airport to watch planes take off and land. He gave me money for an introductory flight at age 15 before I had my first driving lesson. I soloed at age 16 and was hooked."

At Southwestern Michigan College in Cass County, Smiedendorf earned an associate's degree in aviation maintenance and took advantage of its transfer agreement with Western to enter the flight-technology program. "My older brother had attended WMU," he says, "so I had visited the campus several times. I liked what I saw."

He took advantage of the networking opportunities on campus that are available through membership in Alpha Eta Rho, serving as the WMU chapter's secretary his senior year. It allowed him to create valued contacts with fellow students, faculty and aviation professionals aligned with the fraternity that links higher education with the industry.

Smiedendorf formed strong bonds with Ron Sackett, head of the WMU program at the time, and instructor Tom Deckard, whose personal-favorite air-transportation course capped off his degree requirement.

Deckard brought all kinds of perspectives to his students, including those of the head of the air-traffic controllers union at the Kalamazoo Municipal Airport right after President Ronald Reagan's mass firing of the striking federal employees. "Tom was a great flight instructor who made you a better pilot and a better person," he says.

Deckard also shared with Smiedendorf his experience of serving in the Air Force and endorsed the student's application to officer training school. His plan was to attend, move on to navigator training, and then fly for the Air Force. Ah, the plans of mice and men.

"I did not pass my flight physical," he says, "and that would have been the end of my chance to join the Air Force. However, because I had aircraft-maintenance experience and a bachelor's in aviation, the Air Force offered me the chance to get my commission and become an aircraft-maintenance officer. My WMU experience showed me there were many other career opportunities in aviation beyond flying." Mice and men sometimes still end up on the right path.

Before donning those Air Force "blues" in 1985, Smiedendorf sampled life in aviation's private sector, spending part of three years at Bartelt Aviation and one at Fort Wayne Air Service. The former was his first chance to use his A&P (airframe and powerplant) certificate training and work with other mechanics in the field, all of which would serve him well while in the military. In Fort Wayne, he experienced the logistics necessary to get a wounded plane from the shop back into the air.

For the repairs, he needed a part, contacted a vendor in California, and arranged for overnight delivery. "We received the part early the next morning, and the aircraft was back in the air by lunch time," he recalls. Another lesson well learned for an Air Force career.

One of his final assignments was as the chief of aircraft maintenance at "Headquarters Air Force Special Operations Command" in which he was "responsible for 4,000 maintainers supporting 215 aircraft of 17 various types. . .Getting maintainers trained on the new platforms and establishing inspection programs while still supporting the nation's mission in combat was quite challenging," he says.

So was achieving a level of skilled mechanical talent and knowledge in the public sector -- to wit, the Air Force. "The typical Air Force maintainer is not an A&P mechanic," he says. "Rather, they come looking to learn to be a mechanic and are put into specialized segments such as propulsion, avionics, structural repair or hydraulics. You have a high turnover of personnel every year and technicians do not stay assigned to a particular type of aircraft. That's why Western's program is so exceptional with its great faculty and facilities."

Although he's not a one-man band when it comes to honoring a fellow named Charles Taylor, Smiedendorf will often assume the bully pulpit when singing the praises of the Wright brothers' mechanic who built that first engine giving them the capacity to achieve powered flight.

Taylor "is recognized as the Father of Aircraft Maintenance," he says. "There is a bust of him in the Air Force Academy Library right next to the Wright brothers, courtesy of the Professional Aircraft Maintenance Association that I was a part of. Every May 24 is National Aviation Maintainer Day. It is Taylor's birthday." Smiedendorf has also been involved in sponsoring technical competitions and scholarships to advance the competency skills in his profession.

"My parents purchased a picnic table for the break area at the College of Aviation's new facility in Battle Creek," he says. "I also continue to make donations to the program and advise prospective students to give WMU a good look. In all my offices around the world, I displayed Western items, credentials and clothing. Graduating from WMU gave me the foundation to succeed in my career in aviation. I am a proud Bronco alumnus, and I want others to have a similar experience." Such as when he completed his final cross-country flight at Western that took him around Lake Michigan.

Who knows whether Smiedendorf will un-retire in the near future, but he and his wife, Marylou (WMU class of 1984), have plenty to keep them busy -- three grown children and three grandchildren living in Chicagoland. During their Bronco days, both attended WMU hockey and football games. College gridiron matches still attract them.

He plays his share of golf, will engage in long-distance runs, and follows the world of auto racing. For spouses who have filled many a passport during their career's travels, it would seem that "home, sweet home" is in their immediate plans.

Not so. The Smiedendorfs intend to head for Vietnam and Thailand in 2026. And once again, take the brand and message of Western Michigan University with them.